Why 'Taxpayer' Identity And Thinking Is Morally Bankrupt In Every Context

'Taxpayer' identity and thinking is not appropriate even when discussing measures at the state and local levels.

In linguistic studies, we learn about the "denotation" of a word and the "connotation" of a word.

Disaggregating the denotation of the word "taxpayer" from its connotation reveals something very important. This essay will describe why the connotation of the word “taxpayer” is its only relevant definition, it will explain why there is no context in which “taxpayer” identity and thinking are not morally bankrupt, and it will explain why this is so even though state and local taxes - which actually do fund expenditures - tend to be regressive.

This essay is inspired in part by my having seen some people who understand that the sovereign government doesn't spend tax revenue, that the affordability of any national public policy measure is about resources and not about money, nevertheless say that "taxpayer" and "taxpayer money" and “taxpayer dollars” and “taxpayer funds” are still an appropriate descriptions of things at the state and local levels.

To acknowledge that the sovereign government does not spend tax revenue but then say that “taxpayer money” is still a thing at the state and local level betrays a lack of understanding of what "taxpayer" actually means, and I will explain why that lack of understanding is harmful.

A Linguistics Lesson

First, let's review what "denotation" and "connotation" are.

The denotation of a word is the literal or most-nearly-literal meaning or definition of a word devoid of emotion, whereas the connotation of a word is the imagery, emotions, and associations conveyed in the mind of the reader or listener by the word, the feeling of a word, and it is often implied. You could say that the denotation of a word is its objective meaning while the connotation of a word is its subjective meaning.

If you use the word "man" simply to signify an adult male person, then you're using its denotation, but if you're using the word "man" to highlight some positive attributes of an adult male person, especially to compare him to other adult male persons who might be perceived as lacking such positive attributes, then you're using its connotation. We know that to tell someone to "be a man!" - perhaps as a way of encouraging courageousness, even if there are much better ways to do that - is not to tell someone to be an adult male person.

Now, look at the word "taxpayer."

Why Does This Word Even Exist?

Thinking about the denotation, thinking about the purpose of the denotation, of the word should raise your eyebrows.

What is the denotation of "taxpayer"? It is, obviously, "a person who pays taxes."

But then that raises a question: why?

Why would such a word need to exist?

Why would there need to be a noun, let alone an adjective ("taxpayer money"), for a mere denotation of "a person who pays taxes"?

Think about it.

What is the existence of such a word in the first place supposed to suggest? to imply? to convey?

Those additional questions should help to demonstrate that the denotation of "taxpayer" is irrelevant - or, as we shall see, that the connotation is the denotation. The denotation of the word "taxpayer" is stripped of all implications, all cultural and political context, but it's the cultural and political implications of the term – the connotation of the term – that constitute its true meaning.

Even "citizen" signifies exclusions that are problematic, but why would you want to create a separate sub-class among citizens?

Even when limited to citizens, "taxpayer" implies the existence of citizens who do not pay taxes - or, more relevantly, citizens who don't pay as much in taxes as other citizens do, perhaps because they simply don't have enough money.

Why would you want to imply such a thing?

More importantly, what would the effect of implying such things be?

Why not just call them citizens or people?

A Weapon That Works Only When You Are Punching Down

This is where plenty of progressive and liberal people naively think that "taxpayer" is a useful term to use to punch upward against rich people who don't pay taxes. It's not. Don't you want rich people to pay taxes? or more taxes than they already pay? Yes? Then, if so, they would not only become "taxpayers" but would be the ultimate "taxpayers."

As you may have noticed, being a "taxpayer" is a status marker. It's something that middle-class people can share with rich people, which is to say, at the exclusion of poor people, which is how it is extremely useful as a wedge that can be – and constantly is – driven between middle-class people and poor people, and, perhaps just as significantly, to encourage middle-class people to reject policies that would help them, too.

So, "taxpayer" doesn't convey whether one pays taxes as much as it conveys one's capacity to pay taxes, which means that it’s really a way to convey status, which is why using it against rich people whom you want to tax more is a trap that you're setting for yourself. Ultimately, as you will see, “taxpayer” is a way to shame not people who receive but people who most need any kinds of government benefits, and, more importantly, to thereby shame middle-class people into rejecting such benefits themselves. I argue that this is a large and underrated factor in why the United States does not have universal healthcare, and it is underrated simply because it is extremely difficult to measure, because it functions largely subconsciously.

Many of these same progressive and liberal people will say that "everyone pays taxes of some kind" and then go right on using the "taxpayer" phrase.

Again, stop and think about this.

“Taxeater” Is The Hidden Shadow Of “Taxpayer”

If everyone pays taxes of some kind, then, again, what is the point of saying "taxpayer" at all?

Again, the connotation is everything! If everyone pays taxes of some kind, then "taxpayer" is meant to connote "net payers" of taxes - i.e., someone whose tax bill is of more currency than the person supposedly 'gets' - or “eats” - in "government benefits," because we've been conditioned to view both taxes and public benefits in such a way, as some zero-sum transfer between some people and some other people.

As I have argued, this is why many middle-class people who know that they need free healthcare nonetheless are uncomfortable with the idea of universal healthcare, because, even though it wouldn't much or at all alter their tax bill, it would turn them from "taxpayers" into "taxeaters," because too many advocates of universal healthcare accept that framing.

The people who would benefit from universal healthcare but vote against it are not "temporarily-embarrassed millionaires." They are trying to avoid the life-altering social injury of eternal shame that becoming one of the shameful "taxeaters" that most universal-healthcare advocates insist that they become, whether those advocates, at least the ones who dignify the lie that other people’s taxes would fund universal healthcare, realize that is what they are doing.

Advocates of universalist social-welfare policies, like universal healthcare, can try harder to explain to people why they should be willing to become "taxeaters," and then incredulously accuse them of voting against their own interests when those efforts most likely backfire, as they always do, or they can just reject this dumb, destructive framing entirely.

All of these implications both constitute and stem from the connotation of "taxpayer," and that is why the denotation of the word is irrelevant.

Focusing Our Attention Away From The Commons

Furthermore, "taxpayer" and "taxpayer money" condition us to not only view currency as if it is a commodity but, also, to view the outlay of the government - even state and local governments - as stemming from and as being a drain on our "hard-earned tax dollars," rather than something that exists to promote the public good. That is why "public funds" and "taxpayer funds" are not interchangeable. They mean two very, very different things.

The reason that the word "taxpayer" a problem is the deeply problematic nature of the social relations that the word connotes. This is why there is not a word to use in its place, because the whole way of thinking that it evokes is bad.

This poster is Nazi propaganda.

The words read:

60000 RM [currency]

Is what this hereditarily sick person costs to community. Fellow German, this is your money.

Read "Neues Volk" [New Nation/People], the monthly magazine by the ethnic-political department of the NSDAP [Nazi Party].

While this should seem shocking and horrible, and while it is genuinely evil, progressive and liberal people tend to validate its dishonest premise: “I’m happy for my taxes to pay for someone else’s healthcare!”

I have written about how “I’m happy for my taxes to pay for someone else’s _________” is the “as the father of two daughters” of public finance.

I have also written about how the anti-abortion movement and associated bigots like Rush Limbaugh have used “taxpayer” identity and thinking - and progressive and liberals people’s most-unfortunate validation of “taxpayer” identity and thinking - for their own nefarious causes.

But “your taxes” would not pay for anyone’s healthcare, because “your taxes” pay for nothing, because, as should be obvious once you spend a minute thinking about it, sovereign government taxation of currency cannot precede government issue of currency via government “spending.”

Powerful people have consistently and deliberately encouraged us to think of ourselves as “taxpayers,” often both using and fomenting racial resentment in the process, and our willingness to accept the “taxpayer” identity has profound consequences for the ways in which we think of each other.

The Correct Way To Think About Costs Of Public Goods And Services

The cost to society of taking care of the sick and disabled is the opportunity cost of whatever society could have done with the resources – generally, labor – that works to care for the sick and the disabled.

But notice something: in stark contrast to “taxpayer” thinking, that cost is not of something that ever belonged to you or any “taxpayer” in the first place! The government employee who takes care of my disabled cousin was not anyone’s personal, private property in the first place. So, the cost of her taking care of my cousin is not my or anyone else’s currency; it’s whatever else she might be doing for society if she wasn’t taking care of my cousin.

Please recognize the profound difference in thinking here contrasted with the way in which “taxpayer” thinking has brainwashed people. You should view society taking care of the disabled not as stemming from a collection of private resources, of your money and of other people’s personal earnings, but as an allocation of collective resources that never were private in the first place!

No, your taxes do not “pay for” people to take care of my disabled cousin, depriving you of some dessert with your meal from your own hard-earned currency. You “pay for” taking care of my disabled cousin by, say, not having as much cheap labor available for restaurants and bars in my cousin’s town, but, if you have a market income, this cost is somewhat counterbalanced by you being about to earn currency from the spending of the laborers who do the care work in question.

While society taking care of my disabled cousin might cost you, it doesn’t cost you anything that was ever rightfully your exclusive property or possession in the first place.

Where The Wrong Way Of Thinking Leads Us Now

“Taxpayer” thinking encourages us to think of what should be collective public goods as having been stolen from our private wealth portfolios. To say “but I am happy for my taxes to pay for helping people” is only to reinforce the premise of the “taxation is theft” mantra.

And it has some rather harmful effects.

Such classism, ableism, and fascism are where the cringey “pay your fair share” rhetoric and thinking that Democrats robotically spout ultimately leads.

Where could young and impressionable people - people who have yet to develop or crystalize their political identities and affiliations - get the idea that that is how they should think of society and each other? It’s not just people who have conservative or libertarian identity.

This deadly lie, a lie that is one of the founding myths of fascism, is promoted by the Democratic Party.

That this “taxpayer” mythology can be so easily used against those of us who promote a more just and egalitarian society is extremely obvious to our political adversaries.

But the Democratic Party seems to be unable to - okay, unwilling to - stop doing this, and Robert Reich speaks in ways that I would expect a conservative plant in progressive spaces to speak!

The Fallacy Of Money Consumability

Because many services are, under our current arrangements, funded by state and local governments via taxation, we do sometimes have a bit of trouble breaking out of this corrosive way of thinking, though we must remember something that I have long been baffled that even very intelligent people apparently don’t see: that currency does not somehow cease to exist when it is “spent.”

Yes, state and local governments impose taxes and collect US Dollars in taxation, but that currency does not originate with the people, and currency does not cease to exist when people exchange it. State and local expenditures, then, fund the supposedly-aggrieved "taxpayers."

Everyone who has a market income pays taxes on that market income but also benefits from government spending in the form of income; currency that food-stamp recipients, teachers, soldiers, pensioners, and military contractors receive is currency that food-stamp recipients, teachers, soldiers, pensioners, and military contractors spend, and the currency that they “spend” - exchange for goods and services - does not cease to exist when they “spend” it.

That people, even educated and intelligent people, tend to view taxation and government spending as if it were in-kind taxation, as if some of your grain from your own private subsistence farm was taken and given to someone who ate it and converted it to feces, never to return to you as grain, has long baffled me ever since I had my first paying job in high school and started earning currency and paying taxes on it.

I call this strange habit of not including the fact that the currency that governments and direct recipients of government spending spend has to ultimately go to people “The Fallacy Of Money Consumability”. I call The Fallacy Of Money Consumability a strange habit even though I have been able to find only one other person – Steve Roth, publisher of Evonomics magazine, as evidenced by his article “Why Welfare And Redistribution Saves Capitalism From Itself” – who has noticed this ‘strange’ habit.

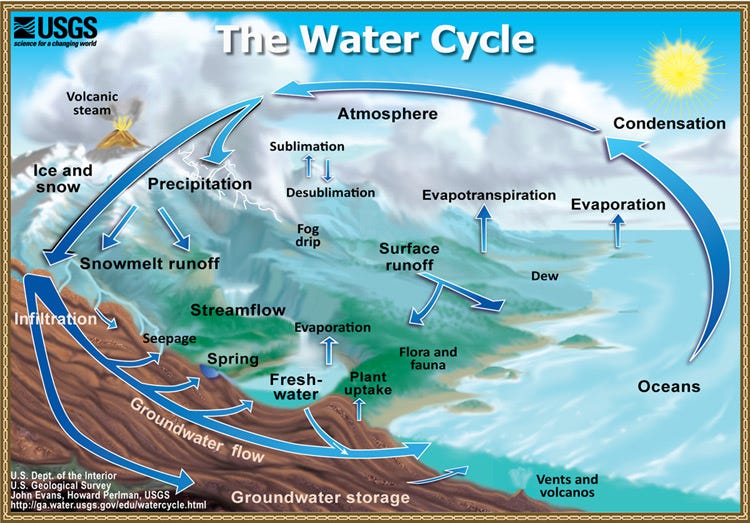

When discussing some policy, we say “but the currency has to come from somewhere”; even if that is true, as it actually generally is for state-government and local-government expenditures, the currency also has to go somewhere, too. It’s a cycle, just like the water cycle.

We don’t say that the oceans and the ground rob the skies of water just as we don’t say that the skies rob the oceans and the ground of water. The quantity of water on Earth is essentially constant.

For some peculiar reason, perhaps due to an adult version of failure to grasp object permanence, we focus only out outflows and pretend that the necessarily corresponding inflows do not exist. The person who survives off of government benefits has no currency at the end of every month, but we pretend that we fund his spending with our tax payments but not that his spending contributes to our taxable income in the first place.

It would be like claiming that your arteries were using your heart to rob blood from your veins, pretending like this process isn’t precisely what supplies your veins with blood in the first place, and the most baffling aspect of this phenomenon is that even people in favor of social-welfare policies dignify this silly premise and act as though a tax to fund something that helps poor people is a noble charity that people should be willing to sacrifice to pay, rather than something that ultimately funds the supposedly-aggrieved “Taxpayer.”

But that is precisely what “taxpayer” thinking does: encourages to myopically focus on outflows in the form of our tax payments to the point of ignoring how government “spending” of currency that it supposedly took from us - and, for state and local governments, that it did indeed take from us - is a large part of what makes the inflows that we have possible in the first place.

So, if you are not prepared to argue that national-government taxation do not fund spending, perhaps because you don’t feel comfortable doing it or perhaps because you’re talking about a state-level expenditure, you can respond to the “where does the currency come from” question by asserting “from wherever it may also go,” forestalling any claim to grievance that the person may have that the expenditure in question would rob him of currency in the form of tax payments.

The Nasty Tax Politics Based On The Fallacy

Oil field workers - to use a good example, since everything runs on oil - gripe that they have to pay taxes “to” fund welfare recipients when much of the oil-field workers' incomes come from the spending of these welfare recipients in the first place; the workers do not fund the welfare recipients any more than the welfare recipients fund the workers, but we – even, paradoxically, social-welfare-policy advocates – pretend that this is not so, pretend that one half of that cycle doesn't exist, and we use "taxpayer" identity as a way of exerting control over poor people, like choosing what foods they are allowed to purchase, because it's supposedly "MY MONEY."

But we don't speak like or act like this in any other context. We don't hand currency to a hairdresser after she just cut our hair and say "that's MY hard-earned money, you better not go spend it on drugs." We don't imagine that either the grocery-store owners or the grocery-store employees had better be good stewards of "our money" that we pay them for food.

By using "taxpayer" in any context, we prop up a couple of core tenets of conservative-libertarian dogma, that, first, money, currency, markets, and even private property somehow pre-exist social organization (and that currency and money are the same thing) and, thus, the state, and, second, that paying taxes is the ultimate expression of citizenship, the ultimate way of "contributing to society," meaning that a wealthy rentier is (at least potentially) more of a "contributor" to society than a migrant laborer who supplies us all with onions but pays little to no currency in taxes is, thus linking one's social standing and social value not with how much one pays in taxes but with how much currency one is capable of paying in taxes.

So, the reason that using “taxpayer” to punch upward at rich people whom you think don’t pay enough taxes doesn’t work is that it is generally in the context of thinking that we could potentially do more with “rich people’s money” if we just taxed them properly, thereby ultimately putting wealthy people on a pedestal and portraying them as society’s ultimate breadwinners. So, while the members of the “make the rich pay their fair share to fund what we need” crowd often complain about others defending rich people, they themselves are the ultimately bootlickers.

The fact that state and local governments tax targets and use the taxed revenue to fund things - a political choice itself, not a result of some law of nature - does not mean that "taxpayer" thinking is appropriate at those levels. No law of nature dictates that schools, local police, or anything else that is currently funded from currency collected by state or local taxation must be funded by state and local taxation, and, still, currency does not cease to exist when state or local governments or the people directly paid by them “spend” it.

Therefore, a complaint about some public expenditure should never be a complaint about some tax to fund it and vice versa; we should speak of a hoped-for world in which currency-issuing governments would fund much of what state and local governments now fund. If someone in your town expresses frustration about being expected to vote for a tax increase to fund local schools, this is a perfect opportunity to remind people that funding schools this way is a political choice, that, while we’re not going to be able to change the way that the whole country does this before the upcoming local election on this tax, we ultimately do not have to create these toxic tax-to-fund fights in every municipality. By advancing this conversation, we can start to break the link in people’s heads between some specific tax that takes currency from them and some specific expenditure that funds other people.

That is why, in every context, the connotation of "taxpayer" is still the same: a transactional worldview that is corrosive to the concept of the public good, that promotes a conservative-libertarian worldview and promotes hierarchy and exclusion. As Myerson and Carrillo write, "If we’re looking out for 'taxpayers' and not the public as a whole, we are favoring wealthier groups over poorer ones—white people over Black people, men over women, U.S.-born people over immigrants, and so forth."

As Elizabeth Bruenig writes, "Along with wrongly dividing the public into various private interest sets, taxpayer terminology also seems to subtly promote the idea that a person’s share in our democratic governance should depend upon their contribution in taxes. If government should respond to the will of taxpayers because programs are incorrectly supposed to be financed on their dime, then those contributing larger shares would seem to be due greater consideration, like shareholders in a company."

This is a profoundly bleak, anti-communal, conservative-libertarian way of thinking, but the Democratic Party encourages it. Imagine someone who wasn’t sufficiently motivated to vote against Trump in November of 2020 seeing this.

Would that person think, “you know, I wasn’t motivated to vote to remove Trump from office, but when I was reminded that he spent my money playing golf, I was”? I don’t think so, but what Reich’s tweet - and there are many of them, because he plays the “taxpayer” game often - does accomplish is to remind people to think of the currency that the government supposedly spends as being theirs, and for that personal-propertarian way of thinking to displace any sense of community in the voter’s imagination.

Trump’s excessive golf trips did not “cost taxpayers” any “money” or currency that they paid in settlement of their tax liabilities.

Trump’s golf excessive golf trips cost human beings whatever could have been done with the land, the labor, and the materials employed in the service of his playing golf, and, furthermore, the liberal focus on supposed theft from our wallets encourages people to think in a manner that has a racist history. Here is a picture that I took 10 years ago today in Amelia, Louisiana.

If Trump’s golf trips are funded by the currency of my tax payments from my hard-earned income from my labor, then so, too, is everything else that the government spends, including on people I might not like, whom I may have voted for Trump in order to harm, people who will - and I cannot stress this enough - be the most harmed by the government’s decision to be stingy.

Elon Musk will not be harmed by the government no longer subsidizing his business like poor people will be harmed by the government no longer funding social-welfare programs.

So, seeing something like what the “Being Liberal” Facebook page, which has 1.7 million followers, posted here might have the effect of just reaffirming a persuadable voter’s decision to vote for Trump or to not vote against him.

If you understand why fat-shaming Trump is harmful, you should understand why memes like these are far more harmful than even fat shaming.

So, you can’t have it both ways. The correct way to think of the cost of Trump’s golf trips is that Trump’s excessive golf trips cost the community resources that are collective in nature. Furthermore, the liberal focus on the supposed outflow from our wallets largely blinded us to the actual crime that Trump was committing: that much of those Treasury payments was going to his family businesses. The victims of that grift were not “taxpayers.”

Well-to-do people simply don’t want you to think this way, because then you’d realize the true cost of all golfing!

So, it’s imperative for us to completely stop thinking and speaking this way, because the results of this way of thinking are deadly and reinforce classism.

The denotation of "taxpayer" raises questions about why the term needs to exist at all. Therefore, the connotation of the word is all that matters, the connotation of the word essentially is - becomes - the denotation of the word, and the connotation of the word "taxpayer" is designed to, at every level of government, poison social cohesion by portraying the public good as coming at the expense of “the taxpayer," thereby encouraging people to reject the public good by thinking in highly individualized terms. It has nothing to do with whether one pays taxes and everything to do with how people are supposed to think about their tax payments and how they are supposed to think of the public good.

In every context, "taxpayer" is a bigoted, classist trope and should be treated as such, because the implications of such thinking are profound and invariably bad.

The framework is malicious - setting individualism to pit against collectiveness. Instead of "Look at how good we are doing as a society", we say, "Look at how much money this is costing US". The idea that the money evaporates and is no longer in circulation is an illusion. Touching back to the beginning of the article - I would love to elaborate on the ways in which it makes contributors FEEL - which pit us against the "taxeaters" (I love this word, btw). Framing who are the real "taxeaters" and link it to globalism and consequences. Anyway - really glad I found this newsletter. Makes me feel less "crazy" for feeling the way I have felt about public funds.

James, I especially love your water cycle analogy. This is really well done.