The National Debt Is GOOD And Necessary - And Calling It 'The National Debt' Is Good

We've been bamboozled into accepting the premise that the national debt is bad, or that it is good but shouldn't be called "the national debt," and the results are profoundly bad.

Even Hunter Gatherers Have A National Debt

When we are born, we are helpless. For many years after that, we are mostly helpless, completely unable to survive on our own. The adults in our lives feed us, shelter us, clothe us, clean our poop, teach us, entertain us, form bonds with us, and love us.

By the time we reach an age and a maturity level at which we can do things for ourselves, we have incurred a great debt. Other human beings have labored on our behalf for years before we start being able to cook, to wash clothes, to repair things, to mop the floor, and, eventually, to hunt and gather food and shelter materials for ourselves and our families – or, to put that in modern-civilizational terms, to get a job, in which we labor to produce goods and services for others, that pays us currency so that we can purchase such materials in our modern markets.

The currency that we are paid is the government’s debt.

How Do We – Or Do We Even – Repay These Debts?

The idea that we have incurred a great debt by the time that we reach our teenage and, especially, adult years seems to be both straightforward and uncontroversial.

But it raises some important questions!

How do we “repay” this debt?

And to whom do we “repay” it?

And, perhaps most saliently, might there be a difference between repaying a debt and paying back a debt?

At first glance, the answers might seem straightforward, obvious, and not particularly relevant. We repay our creditors – our parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles – by taking care of them as they age.

A moment of reflection, though, reveals that this answer is insufficient. Your parents and everyone who did unpaid labor might die as soon as you reach adulthood. This happens to some people. While society affords people who have experienced such tragedies time for grief, do we assume that, once the grieving period ends, these people owe society nothing? Furthermore, some people can maintain remarkable health well into middle age and even the early ‘elderly’ years. Do we assume that a person whose parents have practically no health problems before they die a quick and relatively-easy death at, say, age 65 or 70 do not owe society anything even though their parents almost never have need for their help?

An Idea As Old As Civilization

The late anthropologist David Graeber talked about the cosmic debt described by various ancient religious texts, and how “repaying” some of these debts entails becoming your creditor.

You ‘repay’ your debt to your ancestors by becoming a parent yourself, which then puts your children in such debt to their children.

You ‘repay’ your debt to the sages by becoming wise yourself and teaching future generations, which puts them in debt to teach future generations themselves.

You ‘repay’ your debt to society by doing things for society – thus becoming a creditor for future generations who will never actually repay you, and there is nothing at all bad about this because debt is the basis of human sociality.

“You owe a debt to humanity as a whole for making your life possible. How do you pay it back? You are hospitable strangers,” Graeber said.

It’s Less Of A Metaphor Than You May Think

Maybe this is how we need to think of what we call the “national debt” – the sum total of interest-bearing treasury bills that is the difference between all US Dollars ever issued into existence and all US Dollars deleted via taxation. People still freak out when you explain that the Treasury bonds are just converted back to currency, new debt is issued in its place, and the national debt will never actually be paid off.

But why is this a cause for consternation? I could share what the US Federal Reserve Bank says about why the fact that the national debt will never be paid off is not a cause for concern.

While a household has a finite lifespan, a government has an indefinite planning horizon. So, while a household must eventually retire its debt, a government can, in principle, refinance (or roll over) its debt indefinitely.

Yes, debt has to be repaid when it comes due. But maturing debt can be replaced with newly issued debt. Rolling over the debt in this manner means that it need never be “paid back.”

Even that explanation, while wholly true, is lacking, because the fact that sovereign governments – which are the public authorities over all of society – have an indefinite lifespans is not the only thing that distinguishes public debt from private debt. Household debt is owed to higher powers, powers higher than households, as households are tiny individual production-consumption units within a larger ecosystem and society; household debt is owed to government-chartered lending institutions and governments.

To what higher power, though, is public debt owed? Is it owed to God? Is it owed to some overlords from another planet? Is it owed to some greater entity in the universe?

Graeber spoke of this question, too, that paying off debts to gods and to society usually means becoming a creditor yourself.

I hope that you can see from my own explanation that my explanation of our interpersonal debts throughout our lifetime from birth to old age to death is less of a metaphor for what we call “the national debt” that it may have first appeared, because the actual official “national debt” does constitute debt paid to us by previous generations and debt that we owe to future generations.

Also, if you’re worried about the interest on the national debt, just don’t. As economist James Galbraith has said

In the modern world, when the Treasury writes you a check, your bank credits your account. That's how money creation works. The Treasury then issues bonds to absorb that money. Banks like this because bonds pay more interest than reserves. But there is nothing economically necessary about the bonds. This is obvious since the Federal Reserve buys back many of them, leaving the public with the cash it would have had in the first place.

Could the Treasury skip the rigamarole and pay its bills without bonds? Economically, sure. Why doesn't it? Well, the Fed has regulations governing “overdrafts” -- but apart from these, the answer is plain: to do so would expose the “public debt” as a fiction, and the debt ceiling as a sham.

So, selling bonds is not necessary, but nor is selling bonds much if any problem, since we, as persons in a democracy, are issuers of the debt in the first place.

We Should Stop Trying To Rename The National Debt

In this essay, I am, in order to illustrate an important point, taking a different approach here compared to the approach that many of us who have been trying to educate people that the “national debt” is not a problem have typically taken.

I usually refer to the “national debt” as “the so-called ‘national debt,’” implying that it is not really a debt, at least not in the manner in which most people think of the term. Others who are, like me, trying to get people to stop thinking of the national debt as a bad thing say things like “there is no debt.” Some even say that we should stop calling it “the national debt.” Steve Roth, the publisher of Evonomics, has an article suggesting exactly that, an excellent article that explains why the national debt is a good and necessary thing.

I wonder, though, if running away from the “debt” name may be a wrong and even counterproductive approach. I suspect that even many of the people who logically know that the national debt is not a bad thing don’t emotionally get why it is a good thing.

I disagree with calling net spending a “deficit,” but I am not sure that I disagree with calling the national debt “the national debt.”

The Deadly Republican Game Perpetuates Because Democrats Agree To Play Along

Right now, just as it did during the Obama Presidency, the Republican Party is threatening to refuse to raise the US debt ceiling unless several of its conditions are met, which could have catastrophic results.

How does the Republican Party get away with doing this?

Simple: by convincing people that we have a debt problem and a “deficit” problem.

How does the Republican Party convince people that we have a debt problem and a “deficit” problem?

The answer is infuriatingly obvious: by getting Democrats to agree that the “national debt” and the “deficit” are bad things.

Every damn day, you can get on social media or turn on the television and hear Democrats acting as though the “deficit” is an actual deficit, a bad thing, and the national debt, too, is a bad thing, talking about how the debt is Trump’s and Republicans’ fault.

Here is a meme that you can’t go more than a couple of weeks in the last three years without seeing.

Notice that points 1 through 6 accept the premise that “the debt” is bad. It’s a meme that reflects a total lack of self awareness at the behavior that it is criticizing, because the only reason that Republicans are able to run this playbook in the first place is that Democrats agree that “the debt” is a bad thing and set out to “fix” it – by raising taxes and denying us services, which empowers Republicans.

Once you have conceded that premise, that “the debt” is a bad thing, you have lost, and economist Stephanie Kelton, author of The Deficit Myth, warned us of this more than two years ago.

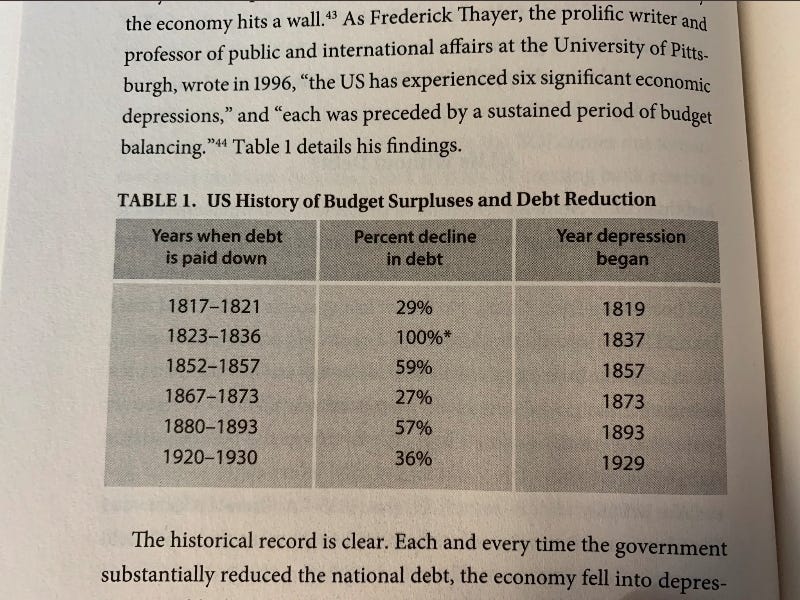

As Kelton shows us in her book, and as many others have pointed out before, all serious efforts at eliminating the debt have resulted in recessions.

Totally on brand, Robert Reich, whom I am halfway convinced was created in a lab somewhere to be a conservative caricature of a liberal person, just reaffirmed Republicans’ premise that the “deficit” is a problem.

Also, all over social media, you can find Democratic-aligned voters sharing a chart that shows that Democratic Presidents extract US Dollars from the economy while Republicans put US Dollars into the economy as if it somehow reflects well on Democrats. This is insane. Every single time that serious efforts were made at “paying off” the national debt, a severe recession resulted.

Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts recently published an op-ed in the Boston Globe entitled “The Republican con on the debt ceiling”.

Her assertion that this is all a con from Republicans is correct, but her own editorial demonstrates that she, too, has fallen for it and, thus, given it more power.

She writes that “Republicans don’t really care about the national debt,” which is true, but then she lists five ways that we could reduce the size of the national debt, indicating that she cares about the national debt.

The details of how you play Republicans’ game do not matter. What matters is only whether you agree to play their rigged game in the first place, because, as soon you dignify their premise that the national debt is a bad thing, the sick, the poor, the marginalized, and the elderly – and the health of the planet – on whose behalf you claim to be fighting have lost.

Prior to her five paragraphs that each suggested ways to reduce the size of the national debt, Warren wrote this:

Here’s the ultimate irony of today’s Republican scam: Without years of Republican handouts to the wealthy, there would be no debt ceiling hostage to take. If Republicans hadn’t spent nearly $2 trillion on the Trump tax cuts and abetted wealthy tax cheats by starving the IRS for a decade, the United States wouldn’t need to raise the debt ceiling this year. In fact, the current debt ceiling would have sustained federal spending well past the end of President Biden’s first term. Any debt crisis today should be laid squarely at the feet of the Republicans who worked tirelessly to help the wealthiest Americans avoid paying taxes.

She never suggests just abolishing the stupid debt ceiling (even Robert Reich is now advocating abolishing the debt ceiling), and she does not question the premise that we have a debt crisis! No, Senator, what is actually the ultimate irony is that, in an op-ed in which you call the Republican obsession with the debt ceiling and the debt a con, you are revealing that you’re one of their marks.

We wouldn’t have to raise the debt ceiling had Republicans not done such and such? Well, so what? It doesn’t take a Harvard banking professor and US Senator to see the fault of that approach. As soon as she left Republicans’ premises unchallenged, and as soon as she essentially affirmed their premises, she has made it very easy to say "if Democrats hadn't spent nearly $2 trillion on universal healthcare and a high-speed passenger-rail system, the U.S. wouldn't need a debt ceiling increase this year."

That is the trap that we are setting for ourselves when we agree that the national debt is bad.

National debt and “deficit” hysteria is of a kind with the horrid “taxpayer” mythology and the monetarist collection-plate narrative that sustains it.

This is less metaphorical than it might seem, particularly when you consider that “national debt” hysteria is employed most often against social-welfare measures.

Fighting On Libertarian Turf Will Never Get Us Anywhere Good

We need each other. We do things for each other. The idea that we can completely escape these social obligations – which is the idea of there being no national debt – is a libertarian fantasy.

Think of the iconic U2 song “One” that was released 30 years ago. The band members have repeatedly said that that line “We get to carry each other” was intentional, that we are not hearing what was supposed to be a “got” when we hear “get.” Doing things for each other, a burden, should be seen as a blessing.

Money currency is debt. For as long as we expect there to be a functioning society, there will be public debt. A private debt is something that you pay “back,” but a public debt is something very different: we pay forward a public debt.

Paying off the national debt is a libertarian fantasy, because it means “we don’t need each other anymore” – and that would be a lie. Furthermore, as mentioned before, actually paying off the national debt results in economic hardship, starving the economy(ies) of currency.

Imagine thinking that there could ever come a day in which we do not need each other anymore.

Currency exists in the first place because people need each other.

Therefore, the “national debt” comes from us doing things for society, from society needing us to do things. We are not burdening our grandchildren by issuing debt except that we are burdening them with the obligation to themselves become creditors for their own grandchildren. This is not a threat to society; to the contrary, it is how society is and always has been sustained.

The National Debt Is Beautiful – And Is Necessary

The national debt is the money currency that we use. Our grandchildren will pay taxes, but the national debt is the currency with which they will pay it! The two things cancel each other out, at least currency-wise. When we are vulnerable and hungry, and someone offers us food, we do not complain that the offer is a burden to us because we will later, due to our consumption of the food, have to poop, something that ends the cycle. We take the food, we survive, and we then, thanks to the energy that we got from the good, do things for others, perpetuating the cycle, later.

So, we add to the national debt by doing important things for our future generations, like building healthcare systems, sustainable infrastructure, and a livable planet.

The national debt is a good thing, and it’s good even that it is and is called a “debt.” Our grandchildren will ‘repay’ the national debt in the same way that they will ‘repay’ the work that their teachers, parents, and coaches did for them.

They will become creditors of future generations.

The existence of something called “the national debt” implies the existence of a “national credit.” They are the same thing! just viewed from different perspectives!

Maybe we need to take back the word “debt” – the basis of human sociality – instead of rejecting it.

We would be actually burdening our grandchildren by not crediting them the national debt.

Wow! James goes long form! Really excellent article, thanks for the nice mention. (I read this post first because the headline sounded like a response to my article… 😁) You should write more long stuff. Just found your stack here, gonna read more and subscribe.

Excellent article, thank you. I'm going to try to use what I've learned here to convince other people and see how persuasive it really is.